Alternative Budapest: A Snapshot of the City’s Hidden Creative Scene

2025. February 6.

Branding: Thoughts on Authenticity, Strategy, Trust and Why It Matters

2025. April 10.In 2016, I joined Szőnyi Kino Garden in its second year, becoming a key member of the founding team and later part of the board of the association running it. What started as a fine arts education organization grew into something much more: a unique short film and animation festival, deeply intertwined with mixed arts and a strong sense of community.

But before I dive into the festival itself, I want to acknowledge the person who first brought the idea to life, Bali Nemeth. My close friend and collaborator, one of the core organizers of the association, is highly passionate about film and animation. It was his vision to introduce these elements to the activities of the camp, first by starting his own photography and animation camp and later by hosting movie nights featuring short films and animations. His dedication led to international festival connections, which in turn shaped the identity of Szőnyi Kino Garden.

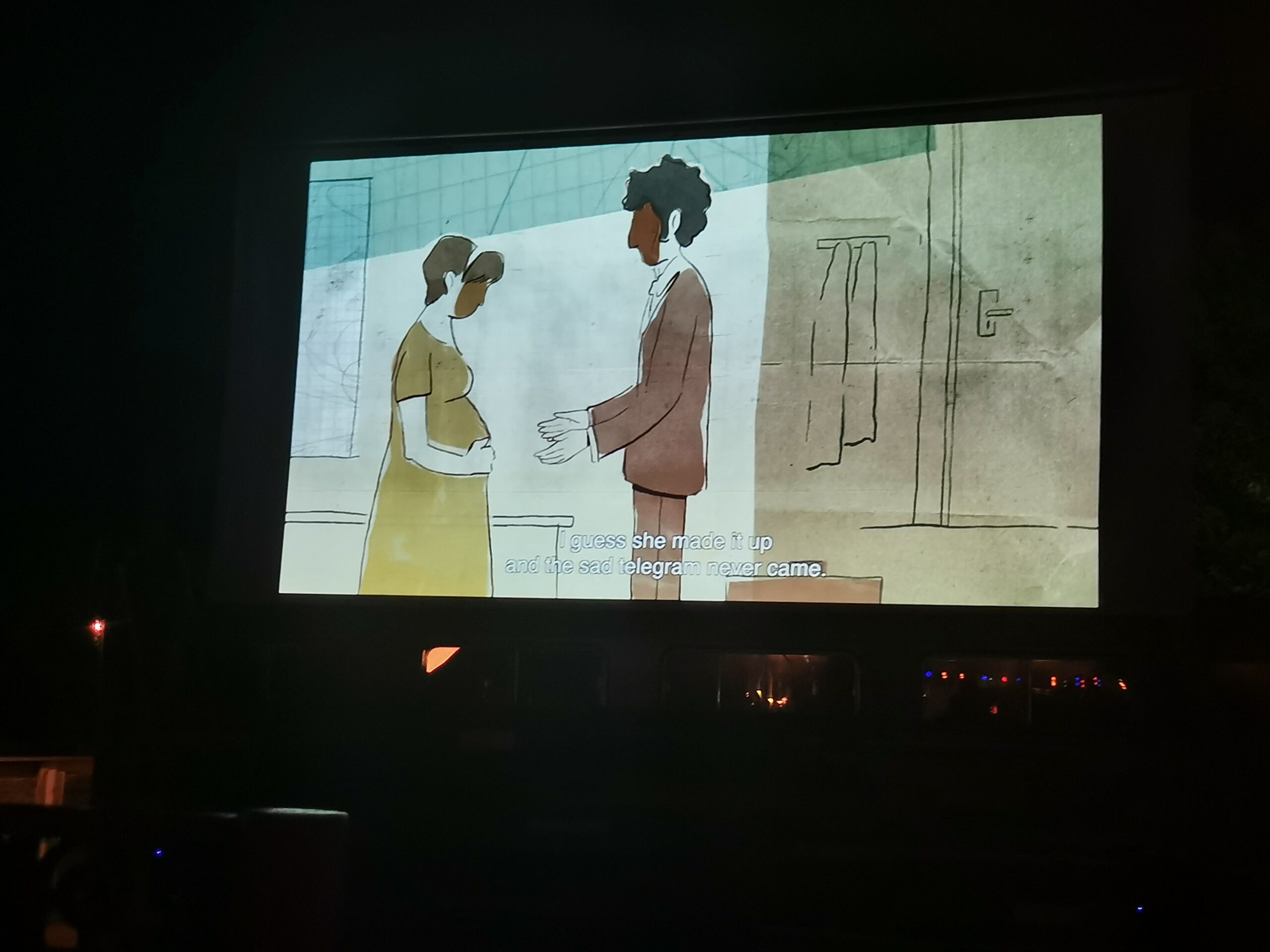

The Art of Short Films and Animation

I truly love this genre. It’s so distinct from feature-length films that it almost feels like an entirely different category. Whether animated or live-action, the limited runtime—typically between 5 and 30 minutes—forces filmmakers to use time in completely unique ways. Some shorts don’t even follow a full storyline, yet they still manage to communicate a complete message. Others work on a purely emotional level, capturing a single idea and stretching it into something profound.

What fascinates me most is the range of storytelling approaches. Some films tell their messages with absolute clarity, even when using abstract metaphors. Others seem simple, yet leave you questioning what you’ve just seen. And then there are those that capture a fleeting moment of reality so perfectly that they feel more real than any feature film ever could. That unpredictability, the ability to evoke powerful emotions in such a short span of time, is what makes this genre so exciting and special to me.

The Process of Selecting Films

Whenever possible, we attended our partner festivals in person to watch their entire selection. If you’ve never been to an official short film competition, it typically consists of 6-12 films per block, with 5-8 blocks screened per day—meaning we were watching hundreds of films over the course of a festival. Each audience member usually receives a voting ticket for every block, so while watching, we were already making notes on which films stood out to us, which didn’t, and why.

When it came the time to curate our own selection from our partners’ films, we had to think beyond just our personal favorites. Our audience and the festival’s overall atmosphere played a huge role in the selection process. Since Szőnyi Kino Garden was a summer, open-air festival with a diverse audience—not just film enthusiasts but also families and children—we had to be mindful of the balance between thought-provoking, experimental films and those that were visually engaging, humorous, or lighthearted. That doesn’t mean we avoided serious films, but we carefully curated the order of each screening block, ensuring that the emotional flow of the evening felt natural. A deeply intense or heavy film placed at the wrong moment could break the atmosphere and send people home before the night’s concerts and social events.

Programming a festival isn’t just about picking great films and performers; it’s about crafting an experience. The selection process was always a creative challenge, finding the right mix that would engage, surprise, and leave a lasting impact on our audience.

A Festival Beyond Film

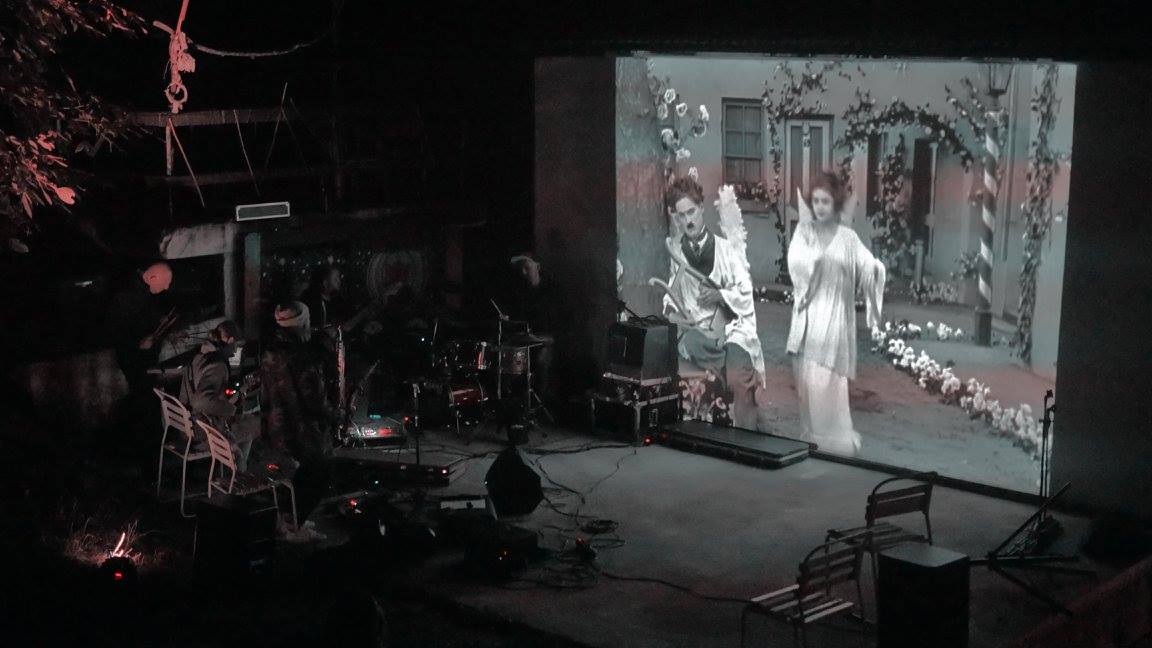

At its core, Szőnyi Kino Garden was a film festival, but what made it unique was its interdisciplinary approach. Unlike most festivals that focus solely on screenings and competitions, we built an event that merged film with other artistic experiences. Since it grew out of a fine arts camp, we naturally incorporated visual arts, workshops, dance, and theater performances before screenings, with concerts rounding out the nights.

The second defining element was community and collaboration. We did not hold our own competition or curate an exclusive selection of films. Instead, we partnered with other film festivals from Hungary, Slovenia, and Poland. These collaborations weren’t just about screenings; they were about building meaningful relationships. Each of our partner festivals had their own dedicated day or weekend, during which we showcased films we’ve had selected together, while also shaping events around their unique identity.

This model allowed us to introduce a wide variety of films and cultures. It was about creating a space where people, ideas, and creative expressions could meet.

An Atmosphere of Freedom and Connection

The atmosphere of the festival was one of its greatest strengths. Held in the Hungarian countryside along the Danube Bend during summer, the setting itself was magical. Our audience, at least in the beginning, was mostly friends, friends of friends, and people with a shared interest in shorts, animation, and arts.

What made it special was the balance of intellectual and free-spirited energy. People were just as eager to engage with niche films as they were to participate in workshops or dance until sunrise. It felt less like a traditional festival and more like a huge backyard gathering—a space where everyone felt at home.

Workshops, Performances, and Unforgettable Moments

Given the festival’s fine arts background, we always made sure to include hands-on creative activities. Music was also a key part of our identity, leading us to curate a well-thought-out lineup each year.

Some of my most memorable moments:

A contemporary dance performance, with just one dancer, no stage, no elaborate setup—only the performer with a costume and a wig and the open ground by the river. It was so powerful that it held everyone’s full attention, proving that sometimes the simplest performances are the most captivating.

An improvised sports competition, where several bands playing that weekend also happened to be good friends. We spontaneously organized games with them as competitors, inventing new sports on the spot, like an inverse swimming contest where the river won. It was one of the funniest, most unpredictable, and joy-filled parts of the festival.

And worth mentioning one more:

At one edition of the festival, held quite literally by the riverside with minimal infrastructure, we relied on a generator to power the stage. In the middle of the biggest concert of the night, as we were constantly running around, we failed to notice the fuel running low—until the generator suddenly cut out, plunging everything into darkness.

What could have been a disaster turned into a moment of pure community spirit. The musicians didn’t miss a beat, continuing to play acoustically with drums and saxophones, while the audience clapped, sang, and embraced the raw energy of the moment. It felt almost tribal, immersive, and electric.

As we scrambled to refill the generator, the atmosphere only intensified. When the power finally came back, it was catharsis, as if the blackout had been part of the experience all along. While not my favorite memory from a technical standpoint, it proved something essential: we had built a community.

Lessons from Our Partners

Our partnerships shaped a lot of what made Szőnyi Kino Garden unique. One of our key influences was Mediawave Festival, another short film and animation festival in Hungary. They had a special way of blending film with music, folklore, and a broader artistic experience. More importantly, they built a true community rather than just an event—a concept we deeply admired.

At Mediawave, there were no strict boundaries between roles. Guests, organizers, and performers all mingled freely. Even meals were communal, with people helping prepare food and sharing long tables together.

Inspired by this, we also experimented with breaking down traditional festival structures, allowing more fluidity between participants and organizers.

Our other partners, Zubroffka and Stoptrik festival, weren’t necessarily shaping our organizational structure, but they were salutary in building meaningful friendships. These relationships reinforced how much collaboration and personal connections matter in sustaining a festival - or any project. A good partnership isn’t just about shared work—it’s about trust, understanding, and the ability to be honest, even in difficult moments. We could be completely open about any problems, whether logistical or financial, without hesitation. Instead of avoiding tough conversations, we faced them head-on, figuring out solutions together.

The same was true for my working partnership with my co-organizer. Being close friends helped us navigate challenges, support each other through difficulties, and stay motivated even when things got tough. That ability to share and open up, to elevate each other when needed, and remain aligned in our goals was invaluable.

Surviving Against the Odds

If I had to name our greatest achievement, it would simply be survival. Year after year, we faced challenges—venue issues, government-related obstacles, financial struggles, and even conflicts within our larger organizing team. Yet, somehow, we always pushed through. What kept me going was my unwavering love for the project and my deep belief in its purpose. But beyond that, it was the bond with my co-organizer that made all the difference. Even in the toughest moments, I never felt alone in the struggle. Whenever I started questioning whether I should stay, it was our shared dedication that kept me moving forward.

A Hidden Treasure and a Full-Circle Moment

One year—I don’t even remember exactly when—we were doing a massive cleanup at the camp, sorting through decades of forgotten objects. It felt like a scene straight out of a movie. We entered a dusty old attic that hadn’t been touched in who knows how long, and inside, we discovered treasures from the past—an old cassette recorder, long-unused tools, supplies, and stacks of original documents from the early years of the association.

As we sifted through the papers, we found something incredible: a document from around 1967, written by the founder of the association himself. In it, he described his vision for the camp—not just as a fine arts education space but as a mixed-arts hub, welcoming music, performance, and even an open-air cinema.

The realization hit us hard. We were already deep into running the festival when we found this, completely unaware that, 50 years later, we were bringing his dream to life. The feeling was indescribable—like history had come full circle, like we were unknowingly carrying forward a vision that had been waiting all this time to be realized.

It was a reminder that sometimes, the things we create aren’t just spontaneous ideas—we might be continuing and working for something much bigger than ourselves.